AI transcript

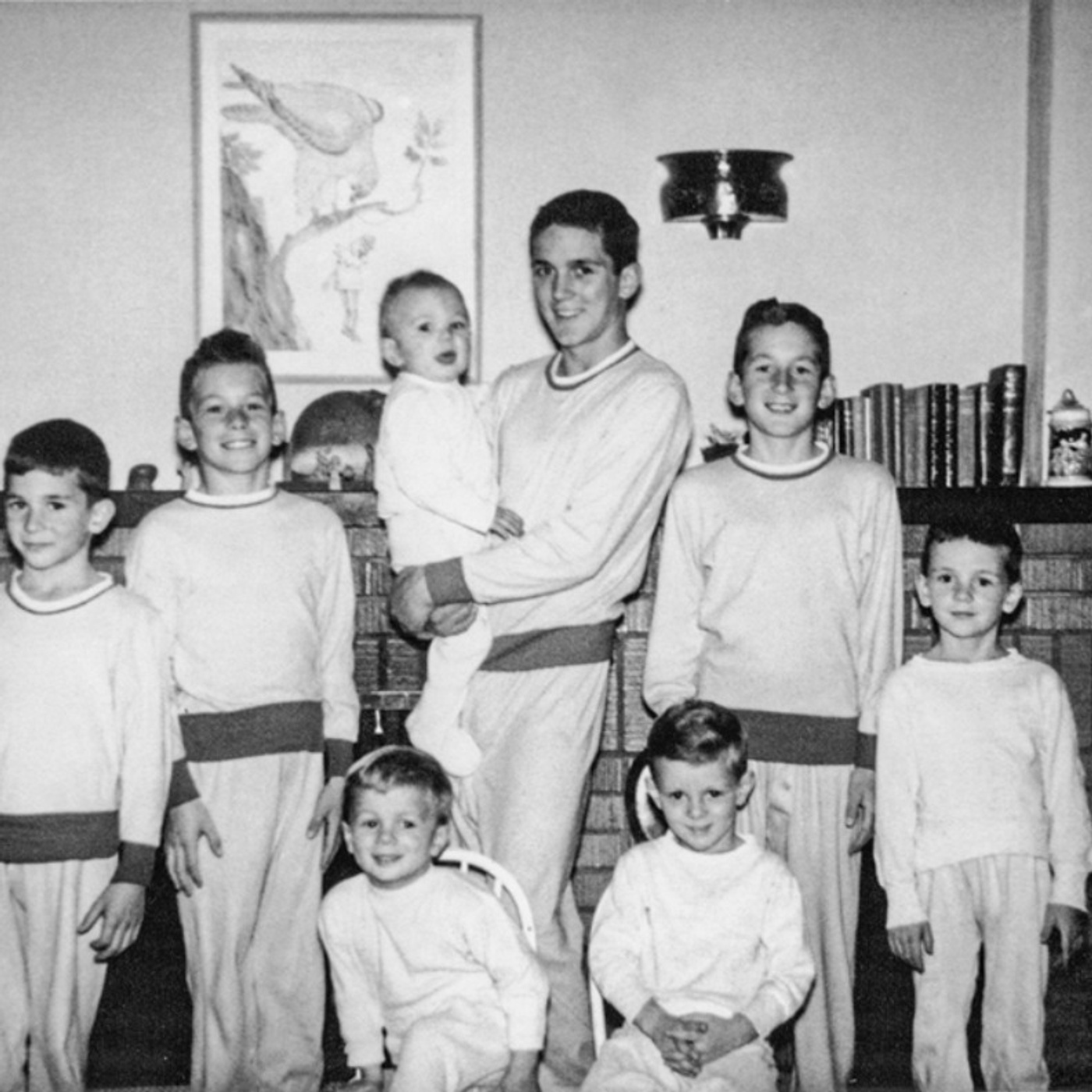

0:00:12 story of one American family, the Galvans, Mimi, Don, their 10 sons, and two girls,

0:00:18 out of whom six sons were afflicted with schizophrenia, following them from the 1950s to today.

0:00:22 Robert Kolker, author of the book and previous author of “Lost Girls,” writes,

0:00:29 “They lived through the eras of institutionalization and shock therapy, the debates between psychotherapy

0:00:34 versus medication, the needle in a haystack, search for genetic markers for the disease,

0:00:38 and the profound disagreements about the cause and origin of the illness itself.”

0:00:44 And because of that, this story is really more than just a portrait of one family. It’s a portrait

0:00:49 of how we have struggled to understand this mental illness, the biology of it, the drivers,

0:00:54 the behaviors and pathology, the genomics of it, and of course the search for treatments that might

0:01:00 help. Also joining Robert Kolker and myself for this conversation is Stefan McDonough, Executive

0:01:05 Director of Genetics at Pfizer World R&D, who is one of the genetic researchers who worked closely

0:01:11 with the Galvans. We start by talking about our attempts to understand and treat schizophrenia

0:01:17 from Freud to lobotomies to the entrance of Thorzine onto the scene, where that understanding

0:01:22 of the disease finally began to shift, especially with new technologies and the advent of the human

0:01:28 genome project, and where we are today in our understanding of the disease, how to treat it,

0:01:33 and where our next big break might come from. What really struck me about this book was that

0:01:41 it was this huge story, not just about one family and this particular disease of schizophrenia,

0:01:46 but also kind of a portrait of our entire effort to understand mental illness period,

0:01:53 and not just how we understand it, but how we experience it and how we try to treat it.

0:01:59 Let’s go back a little bit and talk about schizophrenia itself. I’d love to hear where

0:02:05 you think our modern understanding of the disease really began. You describe a key moment in 1903

0:02:11 where we shift from thinking of it as a religious ailment into something else, or where would

0:02:16 you begin that story? That’s around the time of the dawn of psychiatry as we understand it today.

0:02:21 Obviously, there are glimmers beforehand of people believing that mental illness is physical and

0:02:27 not spiritual or religious, but by the turn of the century, there was an entire field emerging,

0:02:31 and there was a nature-nurture debate over what schizophrenia was that really,

0:02:37 in many ways, continues today in a different form. Back then, the debate was between Freud,

0:02:43 who believed that therapy could cure schizophrenia, that schizophrenia was something that happened in

0:02:48 the nurture side of things, something that happened in your childhood caused it, perhaps bad parenting.

0:02:54 On the other side were a lot of other psychiatrists, including the ones who named schizophrenia,

0:02:59 who believed it had some sort of physical property, but could never put their finger

0:03:05 on what it was. Into this debate come the Galvans, who by the 1950s and ’60s are starting to become

0:03:10 mentally ill at a time where most psychotherapy believes it’s the parent’s fault, and medical

0:03:16 psychiatry is sure that drugs can hit whatever is happening genetically, but they really have no

0:03:21 clue how those drugs work or what genes are really at play, and this continues for decades.

0:03:27 The story of the family starts in the 1950s, but you describe some developments before you

0:03:34 get to this with Dr. Frome Reichman and Gregory Bateson and a couple of other characters that,

0:03:39 to me, felt like kind of key points as our understanding of the disease was developing.

0:03:45 In 1948, Frita Frome Reichman, who was a psychoanalyst then living in America, came up with a term

0:03:51 called the Schizophrenogenic Mother, which she believed was a certain type of mother or father,

0:03:58 in some cases, who was so bad at parenting, was so torturous in the way that they dealt with their

0:04:04 children that the child then would somehow create their own imaginary reality in order to escape from

0:04:11 that parent and become schizophrenic. That was the split. The split was from internal to external.

0:04:15 Exactly. Sometimes people think schizophrenia means split personality,

0:04:20 but it really never did, and it’s really a split between your perceptions of reality and of what’s

0:04:26 happening inside you. Frita Frome Reichman was doing this at a time where lots of psychoanalysts

0:04:32 were blaming mom and dad for lots of things. Of course, by 1960, you have the movie Psycho,

0:04:36 the greatest homicidal maniac in all of cinema. His problem is his mother, and everybody says,

0:04:42 “Oh, yes, that must be what happened.” It seems strange now, but when you think about it back then,

0:04:48 people like Frita Frome Reichman and Gregory Bates, they were doing battle against eugenics

0:04:52 at the time of modern feeling that you could breed out schizophrenia and that you should

0:04:59 sterilize or even euthanize mentally ill people. They were also doing battle with people who were

0:05:04 committing lobotomies and insulin shock therapy and electroshock therapy. They were doing battle

0:05:09 with a medical field that was treating schizophrenic people as subhuman. They felt like they were on

0:05:15 the side of the angels. It was really interesting to me that the kind of duality from Reichman,

0:05:21 her position, on the one hand, having more compassion than anyone had ever really had before

0:05:25 for the people suffering from this disease, but on the other hand, having so little compassion.

0:05:29 For the mothers, it was just a very interesting split there.

0:05:35 Yes, indeed. I think she and a lot of other therapists of her generation were threatened

0:05:40 by changes in society. Women are working after the war. The family unit is being threatened

0:05:46 in some way. The sexual revolution is about to happen. Any major changes in society then began

0:05:51 to be attached to the idea of mental illness until the researchers who went after the Galvin

0:05:57 family who came up in the late ’60s and early ’70s at a time when a lot of established psychiatry

0:06:02 was telling them still that parents were the problem and that working mothers in particular

0:06:07 were the problem. One of the things that really struck me, Bob, was you start in a really interesting

0:06:17 place. You begin with a story of training a falcon and Mimi, you call her a refined daughter of

0:06:23 Texas aristocracy by way of New York, clutching a live bird in one hand and a needle and thread

0:06:30 in the other, preparing to sew the bird’s eyelids shut. Can you tell me why did you start this huge

0:06:36 story about mental illness with this one incredibly vivid and surprising moment?

0:06:43 This took place maybe a week or two after Mimi and her children moved to Colorado Springs in

0:06:48 the early ’50s to join their husband who had just moved there for the Air Force. The whole thing was

0:06:53 unfamiliar to her. It was out of her comfort zone and then to be thrust into this situation where

0:07:00 she was suddenly getting into falconry and having to sew eyelids shut, this was as foreign as it

0:07:05 came to her. The point of the story really is that she accomplishes it. She winds up training and

0:07:12 disciplining the falcon and it winds up becoming almost an allegory for how she approaches the rest

0:07:16 of her life, including the raising of children. She thinks if she tries hard enough, does all the

0:07:21 right things and does them all in the right way with discipline and pressure, she will get the

0:07:26 results she desires. And we all know that with children that isn’t exactly true, but in the

0:07:34 Galvin family’s case, it’s tragically true. 12 children, six of whom had acute mental illness.

0:07:41 And before we get into this particular family and how they dealt with this, I just want to talk

0:07:46 also a little bit about up until that moment, the different treatments that had matched up to our

0:07:51 understanding of the disease that we had tried. You mentioned insulin shock in the 1930s, lobotomizing

0:07:56 attempts and things like that. Can you kind of map out those early therapeutic attempts?

0:08:01 Well, lobotomy is about severing nerves in your frontal lobes. It’s an extreme measure and I

0:08:07 think most people would consider it barbaric now, but it was intended to impair you just enough

0:08:11 so that you would stop hurting yourself mentally. That seemed to be the justification for it at the

0:08:16 time. But the other procedures that you mentioned, things like electroshock therapy and insulin

0:08:22 shock therapy all sort of operate on the same principle, which is to somehow induce enough

0:08:29 stimulation, enough of a seizure, even almost a medical coma, so that you shock the patient into

0:08:35 focusing and not being so distracted or drawn away by whatever is going on with their brain chemistry.

0:08:41 And sometimes it would seem to work at least temporarily, and other times they would decide

0:08:46 that the person needed to be shocked every day. So then in the 1950s, a major development on the

0:08:51 drug side, you talk about the entrance of thorazine onto the scene, which dominates the next

0:08:55 second half of the century and still has a huge legacy in how we handle this

0:09:03 mental illness. Can you talk about what brought thorazine in and what that moment was like?

0:09:08 Like a lot of pharmaceutical advances, it happened sort of sideways or by accident.

0:09:12 There was a French surgeon who was trying to come up with a battlefield anesthetic,

0:09:20 and he did some combining of traditional anesthetic and narcotics and found that the people he was

0:09:26 testing it on, it almost induced a happy coma on them the way that he described it. This drug

0:09:32 eventually was thorazine and even now, really, thorazine is the great advancement pharmacologically

0:09:38 for schizophrenia and still is. And then there’s an atypical version or variety of a psychotropic

0:09:44 drug called chlozapine. And my understanding is that those two drugs really are the coke and pepsi

0:09:50 of this field and that any drug out there is sort of a derivation of one or the two.

0:09:56 There are people who were in such extreme condition and harming themselves so much

0:10:00 that certainly drugs like this could be helpful to them to keep them alive.

0:10:05 But I think the other sad fact is that they aren’t cures and that it’s been decades now

0:10:10 and there really has been no revolutionary drug for schizophrenia since the 1950s and 60s.

0:10:14 The best clue to actually understanding how to attack a disease is have something that cures

0:10:19 the disease, especially something like schizophrenia where the etiology, we may be starting to

0:10:24 understand some of the underpinnings with it, but people don’t come to us at birth and say,

0:10:29 “I’m going to have schizophrenia. Please modify me in some way.” We wait until the symptoms develop

0:10:35 and so exactly as Bob said, it was the cornerstone advance in the field to find a therapy that you

0:10:41 can take as a pill that did in some ways make some patients better. Then you can just simply

0:10:46 reverse engineer that therapy and try to find out on a molecular level what is it doing.

0:10:50 And then that leads to understanding of disease, to dopamine receptors, to serotonin receptors,

0:10:56 and so on. So let’s go back now to that moment in the 1950s which is basically where the Galvan

0:11:03 story starts as well. By the 1960s, the oldest of the 12 Galvan children were starting to go

0:11:08 off to college and as we know schizophrenia’s onset is quite often in late adolescence. And so

0:11:13 the oldest son, Donald, the star of the family, the football star, the guy who dated the general’s

0:11:20 daughter and who was a master falconer and repeller on the cliffs of central Colorado,

0:11:25 he had really had secretly felt quite alienated from mainstream life and really was struggling

0:11:30 in many ways privately and that struggle went public by the middle of college. He ran into a

0:11:36 bonfire and didn’t know why, he tortured a cat and killed it and didn’t know why. He ended up in

0:11:42 student health services for many different reasons until finally psychiatrists got involved. And this

0:11:49 was a panic moment for Don and Mimi Galvan, the parents, because they knew that first of all they

0:11:55 would be judged because at the time if your child had a psychiatric problem it obviously must have

0:12:01 been the parent’s fault. And so they went shopping for a good opinion because back then really what

0:12:06 illness you had psychiatrically really depended on what doctor you visited. Some would say give him

0:12:12 Thorazine, others would say give him a lobotomy. So they went and they found a doctor who recommended

0:12:17 he could go back to college and that he would just grow out of it. And then he got worse and worse

0:12:24 and until finally he had a moment of violence with his young wife, that was it for him. He went off to

0:12:28 the state mental institution for a few weeks and then spent the rest of his life

0:12:34 really at home with Don and Mimi, with his parents, almost as a revolving door between the state

0:12:40 institutions and home. It struck me that every story kind of showed the different lenses that

0:12:47 we’ve used to try and understand this disease. Each had some of these common traits and some

0:12:54 wild discrepancies and differences. A lot of the stories began with we sort of always knew,

0:12:59 but some of them became completely out of left field. And then some of them even seemed like

0:13:05 they come from a cultural moment like Michael who goes to live on the farm in the 1960s.

0:13:09 That’s right. Michael’s sort of a hippie and he is rebelling and then that gets confused with

0:13:16 mental illness for a time. He insists that he is not mentally ill. Peter was very, very

0:13:21 oppositional as a kid said no all the time and then he had psychotic breaks. So you could say

0:13:26 they saw that coming. Joseph had a detachment from reality, it seemed now and then. And so

0:13:31 everybody was sort of waiting for him to finally have a psychotic break and he did in the early

0:13:36 80s. But then there were surprises. Matt, who was a talented ceramic artist suddenly one day out of

0:13:43 nowhere, smashes something that he made and strips naked in a friend’s house and suddenly

0:13:50 he becomes medicalized as well. So it’s interesting how some seem explainable and others do not.

0:13:55 At the same time as we’re hearing this story of how our understanding of the disease changed and how

0:14:02 this one family that manifested so many of those efforts to understand and manage it,

0:14:08 it’s also a story of technology, the developing technology that we have to understand biology

0:14:13 and to understand our brain. Another key moment was when suddenly we start being able to see the

0:14:21 brain through scans in the 70s. Can we go to how this story evolved when that kind of technology

0:14:29 came on the scene? Yes, by the 70s researchers were able to have some glimpses into the brain

0:14:35 thanks to technology, thanks to MRIs and PET scans and CT scans and the like. And with the

0:14:41 sequencing of DNA, it became possible to think about being able to actually study the genetics of

0:14:46 any sort of population of people with any sort of illness or disease. Technology drives biology

0:14:50 across multiple areas. I see that story again and again in whatever field I’m in. You look at the

0:14:55 beginning, the first MRIs, those could only be structure. This might tell you is the structure

0:14:59 of the brain different, but it doesn’t tell you how it functions. It feels like it’s a story about

0:15:04 a family, but it’s also really a story about kind of modern genomics and going from understanding

0:15:11 something as a inherited disease in some way to dialing into a way different level of understanding

0:15:17 about genetic information. So what was the genomic story of what we understood of schizophrenia

0:15:23 pre-Galvin’s? Why was the family such a turning point in the context of the human genome project?

0:15:28 And then what did we learn from them? I write about Robert Friedman, who’s at the University

0:15:34 of Colorado Hospital, and Lynn Delisi, who is at the National Institute of Mental Health.

0:15:38 Lynn’s story really intersects with Stefan’s, my fellow guest on this show.

0:15:44 And before she met Stefan, she was a pioneer in studying families like the Galvans. And the

0:15:49 Galvans were the biggest family she ever found in those early years. And she was convinced that

0:15:54 families were the best way to take a look at this illness because you weren’t searching for a needle

0:15:59 in a haystack. You had a much smaller haystack to look through. They were a closed petri dish of

0:16:04 shared genetic data with a lot of incidents of schizophrenia. Multiplex families like the Galvans,

0:16:09 with lots of schizophrenia in them, have something to teach us. And she amassed the largest collection

0:16:14 of family DNA for this purpose. But there came a time in the ’90s when the human genome project

0:16:19 was underway, when everyone thought that once the genome was sequenced, they’d be able to do

0:16:25 entire population-wide studies. And that anyone with schizophrenia or with any other complex

0:16:31 genetic disorder would sort of stick out like a sore thumb, you would find the smoking-gun gene,

0:16:38 or genes. And then you’d have a target to medicate with a drug. And bingo, we’d all be cured by the

0:16:45 time dinner came. But the problem is that with complex conditions like schizophrenia, it only

0:16:51 complicated things so much more. They found one genetic irregularity for schizophrenia, and then

0:16:57 another, and then another, and then another. Until now, there are far over 100 genetic issues.

0:17:04 Unfortunately, each one of these irregularities contributes just a fraction of a percentage of

0:17:09 the probability that you might get the illness. And so it winds up being meaningless. It strikes

0:17:15 me as just as fluid and complicated and long a list as the list of symptoms that over the last

0:17:21 century have been associated with the disease, the manifestations of it. Exactly. And it’s not

0:17:27 helpful clinically. It might be helpful for future research, but at the moment, it just makes the

0:17:33 mystery more mysterious, which is what makes it so interesting that when Stefan recognized that

0:17:38 families might have something to offer and wondered, hmm, who out there has been studying

0:17:43 families? And lo and behold, there was a woman who had been doing it all this time, and the two of

0:17:47 them teamed up. Stefan, can you talk about what it was like to enter on the scene in that moment and

0:17:54 what the genomic aha was for you there? Yeah, the technology had not been there to really analyze

0:17:59 the families that Lynn collected. She collected them so much before the technology was available to

0:18:04 really look in fine depth at the genome and find, is there something different? Back when I was in

0:18:10 grad school studying genetics, it was mustard weed and fruit flies and sort of model organisms.

0:18:15 When the genomic revolution came along, so much computational power came to be developed. The

0:18:21 technology just kept developing to be able to sequence entire genomes rapidly and inexpensively,

0:18:26 comparatively inexpensively. People sort of thought with a disorder that is so strongly

0:18:33 heritable as schizophrenia, there must be something there. And again, what was turned up in surveys

0:18:38 of tens of thousands of schizophrenia, looking at all the genetic variants they carried versus tens

0:18:44 of thousands of people matched controls as best they could, say for ethnicity and other factors.

0:18:49 No question there are differences. Those have led to some hypotheses, like sort of a general

0:18:55 overall role of the immune system. But in terms of discovering what is the driver

0:19:01 for a disease like schizophrenia, it just simply didn’t work that way. And we still don’t understand

0:19:07 why. Where are we starting to make progress there and understanding kind of the biology

0:19:13 and the drivers and potentially how to treat them? You talked about looking at when a drug

0:19:18 like Thorazine works and trying to work backwards from that to understand more of the biology.

0:19:23 Are we still there or does our understanding of the underlying genomics shifted a bit?

0:19:30 Shifted a bit. I think we’ve gone from a picture of, again, as Bob said, evil spirits or dreams

0:19:36 or some environmental influence or a mother to sort of a holistic picture of the brain whereby

0:19:42 following Thorazine, we would say, okay, well, dopamine is dysregulated or glutamate is dysregulated

0:19:46 and these are chemicals neurotransmitters for how nerve cells communicate with one another.

0:19:53 Now we’re verging towards a sort of cellular synaptic view. Another of the technology that

0:19:59 developed probably in the 80s and especially 1990s was the ability to really look in very,

0:20:05 very fine detail in sort of millisecond scale resolution at how nerves communicate with one

0:20:10 another. You can stick an electrode on one nerve and stick an electrode on the other and really

0:20:15 record how they’re communicating. So this is, I think, how our overall picture of biology is

0:20:22 evolving into as to what it means how we cure the disease. Classic analogy, in order to fix a

0:20:27 broken TV set, you have to know what makes it work in the first place. And we’re still not there,

0:20:32 but we’re getting closer. What is the technology that’s coming onto the scene now that is changing

0:20:38 our potential understanding moving forward? I think one of the areas that’s exciting now

0:20:43 is you can actually take a skin cell from somebody and treat it with appropriate biological factors

0:20:49 and it will differentiate into something that to first approximation might be a human neuron.

0:20:54 I haven’t seen therapies come out of it yet. In fact, it may be another blind alley as with

0:21:00 all areas of research. But there is the hope that if you take a skin cell or a group of skin cells

0:21:06 from somebody with schizophrenia, perhaps that mutation is genetic. Perhaps that mutation then

0:21:12 is still carried in the skin cells and their nerves might look different. So this is a possible angle.

0:21:16 It’s a bit of a risky one for many reasons. You never know if you’re actually dealing with a neuron.

0:21:20 What do you mean by it’s hard to even know if you have a neuron?

0:21:26 Well, you’ve taken a fibroblast, a skin cell, you’ve treated it with appropriate factors and

0:21:31 certainly it elongates, it starts sending out processes and if you can stick an electrode

0:21:36 in it, you can see that it’s electrically active. Does that mean that it really is close enough to

0:21:41 a human neuron in a human brain that has developed through its entire life, through the entire life

0:21:45 of the individual and has been exposed to all the different environmental influences?

0:21:46 Right.

0:21:51 The question isn’t, is one thing like the other? They are like on some level, unlike on others.

0:21:56 Is it enough alike that you could actually try to turn a therapeutic on it and try to do your

0:22:01 modification now you’ve got sort of a disease in a dish? And that’s an open question.

0:22:06 Bob, where would you see the Galvanes their story if it was unfolding today? Can you talk a little

0:22:12 bit about how it kind of mapped to where the understanding is, where their story ended?

0:22:16 Well, the two separate teams who studied the Galvanes, each have come forward with some really

0:22:23 interesting advances, both of which offer a lot of hope. Lynn, Delisi, and Stefan sequenced the

0:22:29 genome of the Galvan family and found one irregularity in a gene called shank 2. This is not a

0:22:34 silver bullet or a smoking gun. It’s not like the shank 2 gene is the ketoschizophrenia. However,

0:22:41 assuming that it is the player that really did its trick on the Galvan family, it is a gene that’s

0:22:45 highly related to brain function and could, with further study, point the way to understanding

0:22:51 how schizophrenia works, how that TV set works, as Stefan had said before. And so that’s exciting.

0:22:57 And more broadly, in terms of drug discovery, families like the Galvanes can be almost sort

0:23:03 of test kitchens. You can look at how their genetic code might interact with certain potential

0:23:08 therapies and see perhaps how it might go with the broader population. Then with that second

0:23:14 set of researchers led by Robert Friedman over in the University of Colorado, he, with help from

0:23:19 the Galvanes and other families, identified another genetic area called churn a seven. And churn a

0:23:25 seven is related to the vulnerability theory of schizophrenia, which is that perhaps one is

0:23:31 oversensitive or has a sensitivity issue to stimuli. It looks at schizophrenia as a developmental

0:23:37 disease, one that really begins in utero even though it manifests itself much later. And over the

0:23:43 years, he struggled to find a way to perhaps make the churn a seven area more healthy or more resilient

0:23:51 and less vulnerable. And he has a hypothesis that there actually is a safe nutritional supplement,

0:23:58 choline can strengthen brain health generally of the unborn child, but also perhaps cross your

0:24:05 finger 16 times, perhaps many years from now prove to make the children more resilient,

0:24:11 less vulnerable to psychosis. And they’re doing longitudinal studies right now using choline,

0:24:15 and if it shows any promise at all, he has the Galvanes and other families like them to thank.

0:24:20 Stephanie, it would be very interesting to hear from your side of the kind of story of the pharma

0:24:26 industry attempt to manage this as well. Where would you see those attempts after Thorzine?

0:24:30 Then where did we go next? And what was the sort of industry response? Where are we today

0:24:34 in the possibility? Yeah, there was a quite productive age where drugs like Cypraxa were

0:24:39 developed, where we’re looking for simply animal behaviors that were related to schizophrenia.

0:24:44 And here is where having sort of a toolkit is quite valuable in a sense, because if you know,

0:24:49 for example, if there’s some odd behavior that an animal is showing that Thorzine mitigates,

0:24:53 then without even knowing the receptors involved, perhaps you can test drugs and animals

0:24:58 for other drugs that mitigate those behaviors and perhaps don’t have side effects.

0:25:03 So the problem, of course, is that rats don’t get schizophrenia. They don’t even have sort of the

0:25:07 massive cortical structures in the folding that we think is where the

0:25:10 higher processes that are affected in schizophrenia reside.

0:25:14 So to your point about cells in a dish, I mean, it’s really a problem of models, right?

0:25:19 It’s a problem of models. How do you, before doing a clinical trial in humans,

0:25:25 how do you get confidence that your drug is going to work? And I think in the 1990s, there were

0:25:29 a number of very good efforts based on sort of synaptic studies. People have known, again,

0:25:34 going back to some of the early pharmacology that dopamine was involved, that glutamate was involved.

0:25:39 Now we started to identify with the human genome project and just molecular cloning in general.

0:25:45 We started to uncover what the molecules are that regulate glutamate and regulate dopamine.

0:25:50 And a number of clinical trials were done on these as well.

0:25:54 What still does stymie the field today is, if you take the overall disease,

0:25:59 what is your model? What do you test it on that gives you confidence that you can test

0:26:01 this safely in humans and that it will have some effect?

0:26:07 How do people even do that? I mean, are there any other tools before you begin clinical trials in

0:26:11 humans when there’s a disease that really doesn’t present anywhere else outside of humans?

0:26:16 Schizophrenia is a tough one. It’s very tough. Now nothing is easy, but for example,

0:26:21 tumors do grow in animals. And you can implant a patient-derived x-plant,

0:26:25 a patient-derived tumor into an animal, and perhaps test therapies there.

0:26:31 Or you do have cancer cell lines, tumors will actually, cell lines will actually grow in a dish.

0:26:35 And so something that kills those could reasonably be called to be acting on the tumor.

0:26:38 And we simply don’t have that equivalent for schizophrenia.

0:26:43 So what was the next moment where there was sort of a something that seemed

0:26:47 on the pharmacology side like a real viable treatment that we were,

0:26:50 you know, that people were getting excited about? And where are we now?

0:26:54 People were excited about metapotropic glutamate receptors. That’s a particular type,

0:26:58 a subtype of glutamate, which is the main excitatory neurotransmitter in the nervous

0:27:03 system in humans. People were excited about sort of finer manipulations of dopamine receptors.

0:27:07 And again, by reverse engineering some of the atypical antipsychotics,

0:27:11 you could find out that serotonin receptors also had involvement.

0:27:15 Now each of these is going to be a broad family of many, many genes.

0:27:22 So can you do more finer manipulations of these? Not every advance in drug therapy has to be a

0:27:29 totally new mechanism. Schizophrenics and other CNS disorders are famous for going off their medications.

0:27:34 So if you can perhaps make a medication that just simply lasts longer

0:27:39 and can be given maybe every month or even at less duration under a doctor’s supervision,

0:27:43 that’s a significant medical advance. And this is an engineering challenge.

0:27:49 I started life as an engineer and drug discovery is really biological engineering.

0:27:53 I’m not saying it’s easy, but we do know how to make drugs last longer in the body.

0:27:56 There’s a very interesting story in there with Nicotine.

0:28:02 The receptor that Robert Friedman in Colorado had identified with help from the Galvin family

0:28:07 and other families like them was a nicotinic receptor. And strictly speaking,

0:28:13 that’s a receptor that when medicated might actually help with focus and concentration.

0:28:18 I mean, there’s a stereotype of schizophrenic patients actually getting some relief from chain

0:28:23 smoking because it focuses their mind. And there’s a hypothesis related to nicotine,

0:28:28 and there was for a time that if you could somehow drug this receptor a little bit to help it along,

0:28:34 that perhaps this would prevent delusions or even prevent psychotic breaks.

0:28:39 And Robert Friedman did try for a while to work on a drug for that, and he reports anecdotal

0:28:45 excellent results from many patients. But it was a drug that you had to take several times a day,

0:28:50 and that was something that the pharmaceutical companies couldn’t bring through trials to make

0:28:56 into a once a day drug. So it went away. So he decided to go after the nicotinic receptor

0:29:04 in utero through choline. Especially in the 1990s, there was a lot of companies and a lot of academic

0:29:10 researchers investigating nicotine and nicotinic receptors. And again, there did seem to be a

0:29:15 clear link to schizophrenia. Perhaps schizophrenics are self-medicating by smoking. If so, perhaps

0:29:21 you can make sort of a subtype of nicotine that gives you some benefit or perhaps even some more

0:29:26 benefit. And again, as Bob said, that perhaps lasts long enough in the body to be practical to

0:29:32 be taken as a drug. So in this case, there was a biological challenge there, no question. But it

0:29:39 became also an engineering challenge, as all drug discovery does. Nicotine is quite a non-selective

0:29:43 molecule. Well, everything it hits is called a nicotinic receptor. But your body has something

0:29:49 like 14, 15 genes for individual subunits that together come together to form a receptor for

0:29:54 nicotine. And they all mix and match in very unpredictable ways and ways that still are not

0:30:01 well known. So the challenge was quite formidable. People did go ahead for technical reasons.

0:30:06 It turned out to be easy to make sort of a subform of nicotine that would only hit Alpha 7

0:30:12 receptors. Not easy, but not impossible either. People had good reason to think that this might

0:30:18 work. No question, it was a huge downer for patients, for the field, for everybody when

0:30:23 this entire class of drugs just sort of didn’t seem to come to nothing. But we learned.

0:30:30 And the negative result often is just as informative as the positive result we do learn.

0:30:37 Can I ask how incentivized is the sort of pharmaceutical industry right now to find

0:30:43 other alternatives to things like the class of drugs that, you know, Thorazine and some others

0:30:48 that you’ve mentioned? I mean, because those do work to some extent, yes?

0:30:53 To some extent. So I’m not a clinician. About 50% of the patients respond well to

0:30:59 atypical antipsychotics. But this doesn’t touch sort of the cognitive and the emotional problems.

0:31:04 And one of the things, one of the many things I’m grateful to Lynn for was really taking me

0:31:10 to visit her patients so that I could really see there’s no question something is wrong,

0:31:16 just sort of a very emotionless, flat affect. The cognition is fine. Clearly,

0:31:21 these people are very articulate. They’re very bright in many cases. But something’s

0:31:27 badly wrong. So to your question, what is the incentive for pharmaceutical companies?

0:31:32 It’s a huge incentive. I think lots of people would love to do it because schizophrenia is

0:31:39 1% of the population. This is across populations, across cultures. So it’s a huge opportunity

0:31:43 to make therapies that help patients. For what is not a rare disease.

0:31:49 For what is not a rare disease. And if you go beyond that, again, as Bob’s book so amply

0:31:56 demonstrates to the toll on people’s lives, it’s far beyond that 1%. We just don’t know how to do it.

0:32:02 Not for the broad schizophrenia there. And this is where I came from my angle

0:32:07 to sort of look at perhaps there might be subtypes of schizophrenia defined by genetics,

0:32:11 where you really would have one particular form of schizophrenia.

0:32:18 So Stefan, if you, as a researcher, if you could wave a magic wand right now,

0:32:24 you know, you mentioned better models. What are the things that if you could wish something here

0:32:29 tomorrow in the form of a new technology or a new capability, what would that be that would

0:32:34 really push us forward into a new chapter? I’ll go way afield. But if we could monitor

0:32:40 the brains of a schizophrenic with sufficient resolution with high resolution, right now we

0:32:46 get about a millimeter voxel with the best bold fMRI experiments. While they’re actually having

0:32:51 a psychotic break, the resolution is still, of course, could be made finer and finer. We still

0:32:56 can’t get down to the level of a single cell. But now with the blood oxygen level dependent,

0:33:02 magnetic resonance imaging, we can get a measure of function in somebody’s brain in real time.

0:33:05 Difficult to do, takes a lot of equipment, takes a particular stimulus,

0:33:08 but one could perhaps hope that this will lead to more insight.

0:33:13 Oh my gosh, how fascinating that we’ve never seen. We actually have no idea what’s really happening.

0:33:18 I mean, consider the logistics. You can’t consent somebody and get them to sit in a machine and

0:33:24 then wait for them to have a psychotic break. Yeah. What would you be looking for?

0:33:31 We need mechanism. If the field as a whole could say, here is a particular area where the excitability

0:33:37 is abnormal, an area of brain tissue that is abnormally excitable, or a particular receptor

0:33:43 that is abnormally excitable, that gives us a good place to start. That gives us mechanism.

0:33:48 And then perhaps we could study what do existing drugs do to that. What is missing with existing

0:33:55 drugs? That’s fascinating. It almost sounds like you need like a wearable MRI, a very high resolution.

0:34:04 Silicon Valley, go to it. What about things like CRISPR? If you do start defining some very specific

0:34:09 narrow, very entirely genetic cause, is that a possibility as well?

0:34:17 So we’ll give a possibility. Say if we knew that a baby galvan or their modern-day counterpart babies

0:34:23 had a variant in a gene that we thought because of families like the galvanes that we had good

0:34:28 reason to believe would make them develop schizophrenia. Can we get in there and change

0:34:36 that one nucleotide to the wild type? It’s conceivable, but again the challenge here is

0:34:43 the engineering challenge. We can do it in a dish, but trying to get just that one gene edited,

0:34:50 trying to get it in just that one nucleotide changed in every cell in the brain and no changes in

0:34:56 any other nucleotides in the brain and delivering something that will actually cross the blood

0:35:02 brain barrier and then doing it on an infant. How would you even test this? Very, very difficult.

0:35:08 Bob, you describe when Lynn Delisi first met the galvan family and you write this incredibly

0:35:12 profound line that really stuck out for me. As she walked through the door of the house at

0:35:17 Hidden Valley Road, she couldn’t help but recognize a perfect sample. This could be the most mentally

0:35:23 ill family in America and you really dove into every element of what that meant for them into

0:35:31 this family’s innermost suffering and struggles. It was just so intimate on some level and also

0:35:36 such a big story on another level of not just schizophrenia, but the way we struggle with

0:35:43 all mental illness, including trauma and depression. What was the kind of big takeaway for you for

0:35:50 having lived inside this family’s mental illness for several generations, really?

0:35:56 Well, I really think the day, hopefully not too long from now, that all this research yields real

0:36:02 rewards will be the day that this family’s sacrifice will finally find its true meaning.

0:36:08 But also, this is a story about experiencing unbelievable and mysterious tragedies one after

0:36:13 the other and coming out the other side. There are members of this family who have found a way

0:36:16 through this and found meaning in life when everything seemed to be going against them.

0:36:22 It’s really about the value of family, in my opinion, this story and the hope for the future.

0:36:26 Stefan, on the research side, what’s coming that we should be aware of that might be

0:36:29 bringing hope to the next generation of Galvans?

0:36:34 It’s tough. I could answer this for Parkinson’s. I could answer for Alzheimer’s. I could answer for

0:36:39 any number of diseases. Schizophrenia is really, really tough. We need some help. We need something

0:36:44 to break in the academic world and that break will come from studying people. There are ever better

0:36:50 ways of studying what is really going on with human biology in people who are kind enough and

0:36:55 selfless enough to volunteer themselves and their families for research. Not just their genome,

0:36:59 we can measure the protein circulating in their blood. There are ways to do this massively in

0:37:04 parallel. Stem cells, organoids, I think it’s too early to see if these are going to be helpful,

0:37:09 but no question, these are a way to explore. People can do longitudinal studies for how people

0:37:14 are changing over time. Imaging lets us look into the brain better than ever before and these

0:37:20 technologies just keep accelerating and improving. We need somebody to set the goalposts. There’s

0:37:26 a lot of advanced technology. Technology will drive biology. We are focused on human subjects.

0:37:32 Something’s got to break. That’s amazing. Thank you so much for both of you joining us on the

0:37:44 A16Z podcast and here’s hoping we get to that break soon.

Descriptions of the mental illness we today call schizophrenia are as old as humankind itself. And more than likely, we are are all familiar with this disease in some way, as it touches 1% of us—millions of lives—and of course, their families. In this episode, we dive into the remarkable story of one such American family, the Galvins: Mimi, Don, and their 12 children, 6 of whom were afflicted with schizophrenia.

In his new book, Hidden Valley Road: Inside the Mind of an American Family, Robert Kolker follows the family from the 1950s to today, through, he writes, “the eras of institutionalization and shock therapy, the debates between psycho-therapy versus medication, the needle-in-a-haystack search for genetic markers for the disease, and the profound disagreements about the cause and origin of the illness itself.” Because of that, this is really more than just a portrait of one family; it’s a portrait of how we have struggled over the last decades to understand this mysterious and devastating mental illness: the biology of it, the drivers, the behaviors and pathology, the genomics, and of course the search for treatments that might help, from lobotomies to ECT to thorazine.

Also joining Robert Kolker and a16z’s Hanne Tidnam in this conversation is Stefan McDonough, Executive Director of Genetics at Pfizer World R&D, one of the genetic researchers who worked closely with the Galvins. The conversation follows the key moments where our understanding of this disease began to shift, especially with new technologies and the advent of the Human Genome Project—and finally where we are today, and where our next big break might come from.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.