Would you be happy with $1 billion? What if everyone else has $100 billion?

The answer reveals something uncomfortable yet profound about human nature: happiness is fundamentally relative. We don’t evaluate our lives by objective standards but by constant comparison to those around us. And in an age of unprecedented wealth inequality and social media exposure, this psychological quirk is making us increasingly miserable.

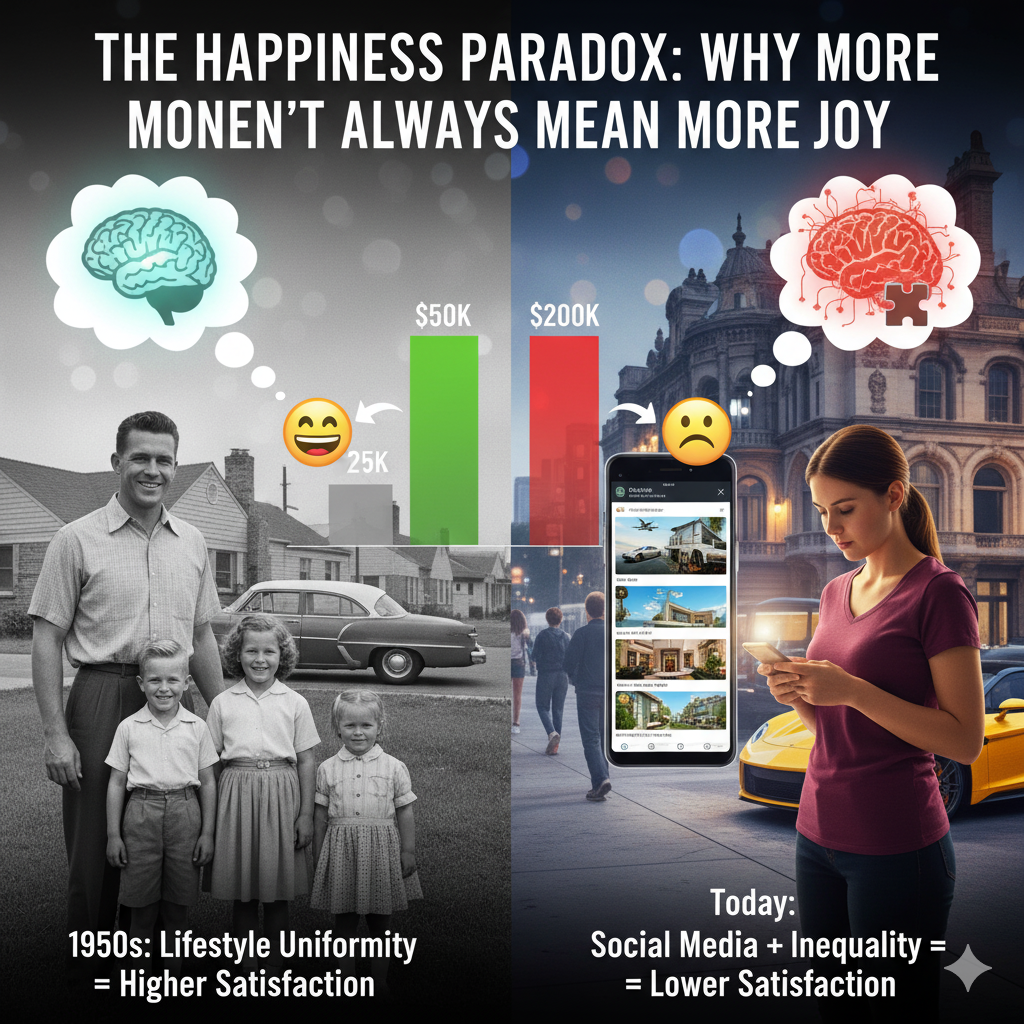

The Mid-Century Happiness Paradox

In The Psychology of Money and in his conversation with Andrew Huberman, author Morgan Housel offers a striking observation: people in the 1950s and 1960s reported higher levels of life satisfaction despite having far less material wealth than we enjoy today.

His explanation? Lifestyle similarity.

In the mid-20th century:

- Most middle-class families lived in similar modest homes

- They drove comparable cars (often the same models)

- Career trajectories and income levels followed predictable, similar paths

- Visible extremes of wealth were rare in everyday life

“When everyone lived in similar houses and drove similar cars, it was easier to feel satisfied,” Housel notes. There simply wasn’t the constant exposure to vastly superior lifestyles that defines modern life.

Today, we have more square footage, better cars, smartphones that contain more computing power than NASA used to land on the moon; and yet, we’re not happier. In fact, by many measures, we’re more anxious, stressed, and dissatisfied than previous generations.

The Psychology Behind Relative Happiness

This isn’t just anecdotal observation. Multiple psychological frameworks explain why comparison destroys contentment:

Social Comparison Theory

In 1954, psychologist Leon Festinger discovered something simple but profound: we don’t judge ourselves in isolation. We judge ourselves by comparison.

As discussed on Jay Shetty’s On Purpose podcast, we don’t compare our lives to who we were yesterday. We compare them to who everyone else is today, or at least what they tell us they are.

You might feel fine about your career until you see a classmate on LinkedIn with a fancy new title. You might feel proud of your apartment until a friend buys a house. You might feel good about your relationship until you scroll past engagement photos.

The Harvard Study That Proves the Point

Here’s a study that stops people in their tracks: Harvard researchers gave graduating students two options:

- Option A: Earn $50,000 per year while everyone else earns $25,000

- Option B: Earn $100,000 per year while everyone else earns $200,000

Which would you choose?

Most students chose Option A—less actual money, but more status relative to others. They’d rather have half the absolute income if it meant being comparatively wealthier than their peers.

A 2010 study by the University of Warwick confirmed this finding: life satisfaction is more influenced by relative income (what you make compared to your peers) than by absolute income.

The Wealth Paradox: Why Rich People Aren’t Happier

If relative comparison drives happiness, you’d expect wealthy people to be consistently happier than everyone else. But they’re not.

In a conversation about happiness on the Huberman Lab podcast, Yale professor Dr. Laurie Santos (host of The Happiness Lab) explains why:

“One of the ways we evaluate our financial situation, but pretty much every situation, is that we don’t do it objectively; we do it relative. And when you think about your relative financial status, there’s lots of other folks around to whom you’re comparing yourself.”

Santos recounts interviewing Clay Cockrell, a wealth psychologist who works exclusively with the ultra-wealthy (the 0.0001%). If wealth made you happy, Cockrell should be out of a job. Instead, he has plenty of clients because wealthy people suffer from the same comparison trap.

They set goals like “Once I have $50 million, I’ll be happy” or “Once I become a billionaire, I’ll feel secure.” But when they reach those milestones without the expected happiness boost, they don’t abandon the hypothesis. Instead, they simply move the goalposts: “Actually, I need $100 million” or “I need to be a multi-billionaire.”

As Santos puts it: “We constantly compare ourselves against others, but we never pick people that are doing worse than us. We always pick people who are doing better than us.”

The Modern Context: Social Media Amplifies Everything

If relative comparison has always been part of human nature, why does it feel more acute now?

Social media has weaponized comparison.

According to a study in Computers and Human Behavior, time spent on social media correlates directly with increased feelings of inadequacy due to comparison. Instagram doesn’t show you the neighbor with a slightly nicer car; it shows you influencers with private jets. LinkedIn doesn’t show you colleagues with marginally better titles; it shows you 25-year-old startup founders raising Series B rounds.

As Dr. Laurie Santos notes, even though we have unprecedented wealth by historical standards, “as you get richer, you’re kind of going up this sort of logarithmic scale where the reference points are getting even further away from you.”

The comparison treadmill speeds up the more successful you become.

What Actually Drives Happiness?

If circumstances and wealth don’t determine happiness as much as we think, what does?

Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman distinguished between two types of happiness:

- Emotional happiness: How you feel when you live day-to-day

- Life satisfaction: How you feel about your life when you think about it

In a podcast with Shane Parrish, Kahneman revealed: “Happiness is mostly social. It’s being with people you love and who love you back. That’s a lot of what happiness is. Life satisfaction is much more conventional—it’s to be successful. It’s money, education, prestige.”

The Harvard Study of Adult Development, which tracked people for over 85 years, arrived at the same conclusion. Dr. Robert Waldinger, the study’s director, summarizes 85 years of research in one sentence: “Good relationships keep us happier and healthier. Period.”

Not money. Not career success. Not material possessions. Relationships.

Breaking Free from the Comparison Trap

So what can we do about this?

1. Recognize That All Behavior Makes Sense With Enough Information

As Housel explains in his Huberman Lab conversation, “All behavior makes sense with enough information.” People spend and save money based on their unique experiences, upbringing, and circumstances.

“It forces you to realize that there is not one right way to manage money, to save it, to spend it,” Housel says. “You got to figure out what works for you and what works for me might not work for you.”

This mindset makes you less cynical about other people’s choices and, importantly, less prone to using them as comparison points.

2. Calibrate Your Sense of Future Regret

When Housel asked Daniel Kahneman about financial decision-making, Kahneman said the most important trait is “a well-calibrated sense of your future regret.”

In other words: What will you wish you had done?

Not: What will look impressive to others? Not: What will make you seem successful? But: What will you personally regret not having done?

This shifts the frame from relative comparison to personal values.

3. Curate Your Reference Points Carefully

As Jay Shetty warns on his podcast: “Be careful who you spend time with, because you will use them as your benchmark for success and happiness.”

If you spend all day on social media following billionaires and celebrities, those become your reference points. If you spend time with people focused on meaningful work, deep relationships, and personal growth, those become your benchmarks.

Your happiness is partly a function of who you compare yourself to. Choose wisely.

4. Focus on Absolute Improvements, Not Relative Position

Am I healthier than last year? Am I more skilled in my craft than last year? Are my relationships deeper than last year? Do I have more freedom than last year?

These questions orient you toward personal progress rather than social comparison.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Here’s what makes this topic difficult: the drive for relative status isn’t just a quirk we can think our way out of. It’s deeply embedded in human psychology, likely because for most of evolutionary history, relative status directly determined access to resources, mates, and survival.

But recognizing this tendency is the first step toward managing it.

As Dr. Laurie Santos puts it: “It’s much less about our circumstances than we think when it comes to who’s happy and who’s not. It tends to be the kind of stuff that’s much more under our control than our circumstances—how we behave, what thought patterns we use, the emotions we seek out, the social connection we experience.”

Happiness will always be relative. But what we’re relative to? That’s something we can choose.

References

- Housel, Morgan. The Psychology of Money. Harriman House, 2020.

- Morgan Housel on the Huberman Lab Podcast: Understanding and applying the psychology of money

- Dr. Laurie Santos on the Huberman Lab Podcast: How to achieve true happiness using science-based protocols

- Jay Shetty’s On Purpose: Stop Comparing Yourself

- Daniel Kahneman on The Knowledge Project: Algorithms make better decisions than you

- Harvard Study of Adult Development, Harvard Gazette

- Festinger, Leon. “A Theory of Social Comparison Processes.” Human Relations, 1954.

- University of Warwick study on relative income and life satisfaction, 2010.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.